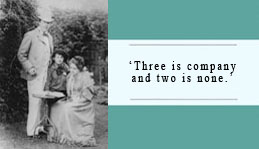

left: Oscar and Constance Wilde with their son Cyril in 1892, © Merlin Holland

right: Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie), photographed at Magdalen College, Oxford in May 1893, © National Portrait Gallery

Oscar Wilde

When Oscar Wilde married Constance Lloyd on 29 May 1884, he was a few months short of his thirtieth birthday, and Constance was twenty-five. Although Wilde was well-known as a wit and a lecturer – and for his colourful and a flamboyant personality – his writings had not yet made much impact. He had written two plays, Vera, or the Nihilists in 1880, and The Duchess of Padua in 1883, but these melodramatic tragedies had attracted little interest. Vera ran for one week in New York in 1882 and The Duchess of Padua was not staged until 1891, when it had a three-week run, again in New York. Wilde had also been writing poetry since he was an undergraduate at Trinity College Dublin, and in 1881 he had published a collection of his verse. But literary fame still lay several years ahead.

Although it was more than a marriage of convenience, there were practical reasons for Wilde to marry, including the increasing amount of gossip about his sexuality. In addition Wilde’s finances were in poor shape. In the Victorian age the financial situation of a potential bride was rarely irrelevant in upper-class families, and Constance had a decent income. She was also attractive and intelligent, and Wilde seems to have been genuinely in love with her – or thought he was, which comes to much the same thing. But he was not suited to fidelity or indeed to the institution of marriage; and in the event the love of his life was to be not a woman but a young man.

There are differences of opinion about when Wilde first had sex with another male. Certainly there were some intense emotional entanglements with young men as far back as his student days, but there is no proof that these became physical. Both Wilde and Robert Ross – the most loyal of Wilde’s friends, and later his literary executor – said that Wilde’s earliest homosexual experience was the first time he had sex with Ross, then aged seventeen, in 1886. As far as sexual relations with women are concerned, Wilde does not seem to have had sex with a young woman of his own class prior to his marriage, although he had undoubtedly used the services of female prostitutes.

Wilde may have posed as a number of things, but he was not a poser when it came to his love of beauty. Indeed his sensibilities in this regard were one of the reasons that his marriage to Constance so quickly failed. Although he later came to see beauty – as far as the erotic was concerned – exclusively in the form of boys and young men, when he first knew Constance she was a very beautiful woman. Had she, like Wilde’s character Dorian Gray, possessed the miraculous gift of never aging, the marriage might have worked for longer. But, fastidious as he was about beauty – more fastidious in the case of women than of young men – he quickly found Constance physically repellent, as he told Frank Harris many years later:

When I married, my wife was a beautiful girl, white and slim as a lily, with dancing eyes and gay rippling laughter like music. In a year or so the flower-like grace had all vanished; she became heavy, shapeless, deformed: she dragged herself around the house in uncouth misery with drawn blotched face and hideous body, sick at heart because of our love. It was dreadful. I tried to be kind to her; forced myself to touch and kiss her; but she was sick always, and – oh! I cannot recall it, it is all loathsome. … Oh, nature is disgusting; it takes beauty and defiles: it defaces the ivory-white body we have adored, with the vile cicatrices of maternity: it befouls the altar of the soul.

(What, it might be asked, did Wilde’s mirror by this time tell him about himself?)

This terrible account, although doubtless embellished by Harris – his memoirs of Wilde include improbable quantities of direct speech – rings largely true. It should, however, be noted that Wilde was speaking in exile during the last few years of his life, when his view of Constance was coloured by the bitterness of estrangement and by disputes about money. He was therefore being extreme and unfair, just as he was in his account of Lord Alfred Douglas in the long letter known as ‘De Profundis’, written in Reading gaol at a time when he wrongly believed that Bosie had abandoned him.

There are two pieces of evidence which confirm that the sexual side of the Wildes’ marriage was brief. The first is the comment, years later, of Constance’s brother Otho that around 1886 there had been a ‘virtual divorce’ between his sister and Wilde, an expression that indicated the end of sexual relations. The second is that in June 1897, after the poet Ernest Dowson had persuaded Wilde to avail himself of the services of a female prostitute in Dieppe, Wilde told Dowson that it had been his first experience of sex with a woman ‘these ten years’.

Thus, although Wilde was still able to perform in the marriage bed after his elder son Cyril’s birth – his second son Vyvyan was conceived in the spring of 1886 – there seem to have been no sexual relations between Oscar and Constance after Vyvyan’s birth on 3 November 1886. Indeed, allowing for the period when Constance was pregnant with Vyvyan – Wilde would not have engaged in marital relations once pregnancy became evident – we may assume that the Wildes’ marriage functioned sexually for less than two years.

Therefore, while there are various ways in which Lord Alfred Douglas could be argued to have stolen Oscar from Constance, he was certainly not responsible for Wilde’s abandonment of the marital bed, which had happened some five years before they met. In any case, as we shall see in a moment, the sexual side of Bosie’s and Oscar’s relationship was itself brief. What in due course became hurtful and humiliating to Constance was to see Bosie usurp other important parts of her marriage, such as intellectual companionship and emotional support.

Indeed, in spite of her suddenly falling in love in the summer of 1894 with the book-seller and part-time publisher Arthur Humphreys, as we shall see in Chapter 6, nothing that we know of Constance suggests that the cessation of sexual relations would itself have been particularly upsetting to her.

But the fault-lines within the marriage were not just to do with Wilde’s having quickly found his wife sexually unattractive; it is hard to see that the marriage would anyway have flourished indefinitely. Being married to a self-absorbed genius is never easy, and Wilde and his wife were in many ways not well-matched. Constance’s nature was more serious than that of her husband. Her younger son Vyvyan later wrote of her: ‘She may not have had much sense of humour, but then she did not have very much to laugh about.’ In addition, Constance became increasingly religious as the years passed, and close proximity to someone with an earnest and all-consuming faith is irksome for those that take a sceptical approach to religion, as Wilde did:

Religion does not help me. The faith that others give to what is unseen, I give to what one can touch, and look at. … When I think about Religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for those who cannot believe: the Confraternity of the Fatherless one might call it.

During the early years of the marriage, however, Wilde and Constance were happy. They had shared pleasures, including the creation of the interior of their ‘house beautiful’ at 16 Tite Street in Chelsea. And Wilde began to find literary success. In 1888 he published a book of stories for children, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, followed in 1890 by his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which attracted a great deal of attention, much of it hostile, on account of its unmissable homoerotic sub-text. The year 1891 saw the publication of two collections of short stories for adults, Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories and The House of Pomegranates, and Wilde’s three most famous essays, ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’, ‘The Decay of Lying’ and ‘The Critic as Artist’, the last two in a collection entitled Intentions. In 1891 Wilde also wrote again for the stage, the result being the one-act tragedy Salome, written in French. It was not produced until 1896, in Paris, by which time Wilde was in prison.

It was during the productive year of 1891 that Wilde first met the Marquess of Queensberry’s son Lord Alfred Douglas, who was always known as Bosie, his nickname in the family as a child. They were introduced by Douglas’s slightly older cousin, the poet Lionel Johnson, who was himself in love with Wilde. Johnson had lent Bosie his copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray, which Bosie read numerous times and which made a great impact on him. It was one afternoon in late June or early July 1891 that Johnson took Bosie to tea at the Wildes’ house in Tite Street. According to Bosie, there was nothing exceptional about this first meeting:

What really happened, of course, at that interview was just the ordinary exchange of courtesies. Wilde was very agreeable and talked a great deal. I was very much impressed, and before I left Wilde had asked me to lunch or dinner at his club, and I had accepted his invitation.

However Bosie says that at their second meeting a few days later Wilde made sexual advances. There is little reason to doubt Bosie’s claim. By this time Wilde rarely delayed when he found a young man attractive, and even before they met he would have been aware from Lionel Johnson, also homosexual, that Bosie’s sexual nature was similar to theirs – too similar, in fact, since Bosie’s own preference for youth and beauty meant that that he did not find Wilde attractive.

In spite of this early attempt on Bosie, Wilde’s and Bosie’s friendship did not develop its special intensity for almost a year, although they saw each other a few times over the intervening period.

In the meantime Wilde had his first stage success, Lady Windermere’s Fan, first performed on 22 February 1892. The play had two West End runs and also toured the provinces, and in the first year Wilde earned something like £1,600 from it (about £160,000 today). A Woman of No Importance (first performed on 19 April 1893), An Ideal Husband (3 January 1895) and The Importance of Being Earnest (14 February 1895) followed in quick succession. Wilde had finally found the genre that was to give him literary immortality – just before his world fell apart.